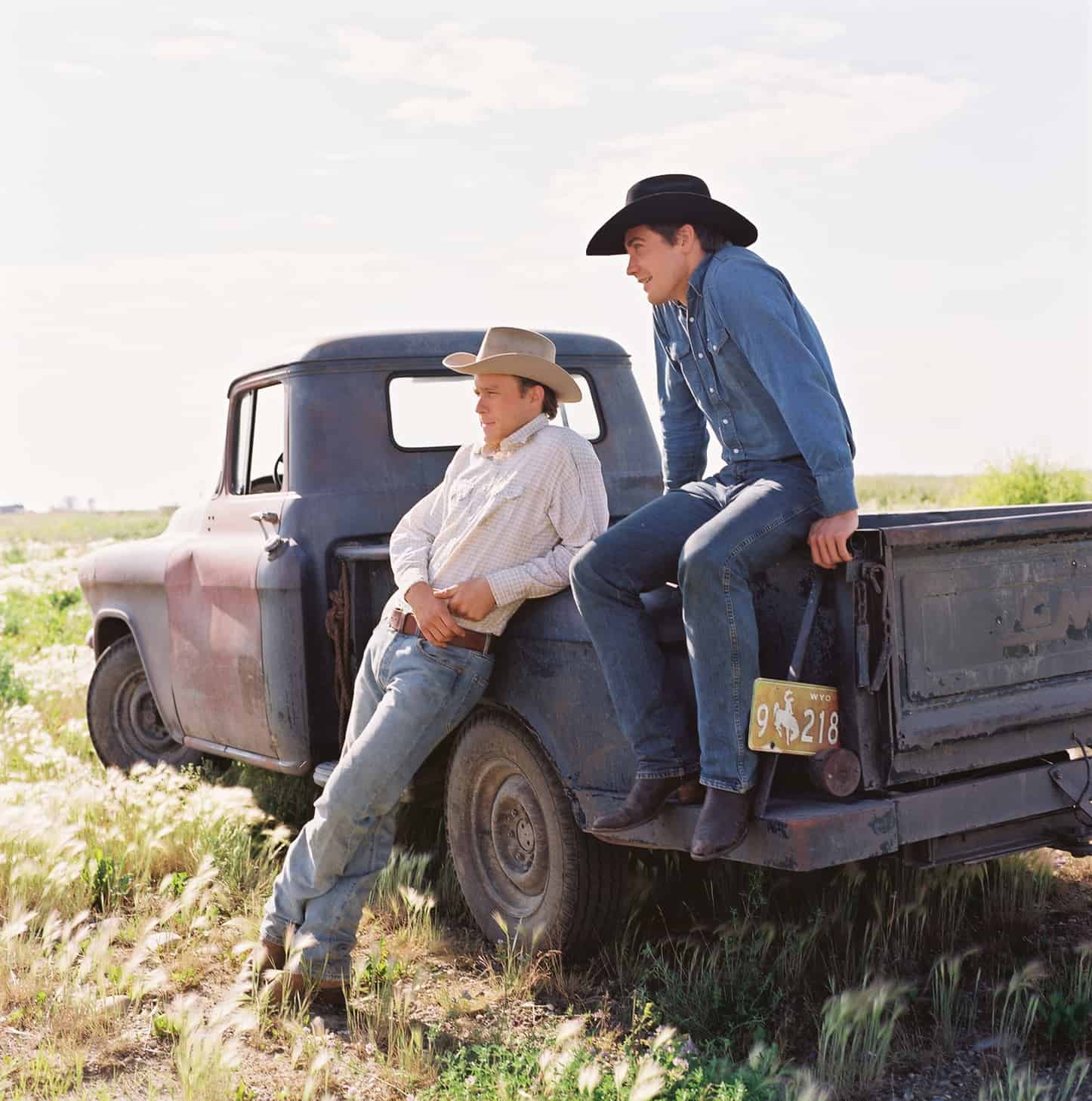

Brokeback Mountain, dir. Ang Lee, 2005.

1. Actual visibility

Out of sight out of mind – this proverb can be applied to many things, queer representation included. Humans are visual creatures; we learn and process best when we’re presented with a picture. That’s why film is such a strong medium: it makes use out of our most dominant sense. It’s especially clear when it comes to the representation of non-heteronormativity on the silver screen. Throughout the years, cinema has been a tool which both empowered and disenfranchised those who didn’t quite fit under the umbrella of what’s ‘regular.’ On one hand we have dark moments in the history of filmmaking such as The Hays Code which for over three decades ensured censorship of everything that was deemed immoral (especially LGBTQ-related themes), and on the other – there are countless examples of challenging the status quo and fighting for visibility – let’s not forget about My Own Private Idaho (1991, G. Van Sant) and Moonlight (2016, B. Jenkins), two films that rose against all odds and struck a chord with audiences worldwide. Queer figures in film, such as Andrew Beckett from Philadephia (1993, J. Demme), struggled for their right to take up space onscreen precisely because being seen is just one step away from actually being noticed, and then – from being understood. What we see becomes a part of our reality and is usually easier to understand, and to accept.

2. Reach

Film as a business is still one of the most fruitful branches of entertainment, bringing in worth as high as 34 billion GBP world-wide last year (and that’s excluding streaming services), which translates directly into the size of the audiences. If we want to tell stories of people whose voices have been silenced for years on end, is there any better way to do it than through the lens of a film camera? There’s no other form of art out there than can package and ‘sell’ the subversive in such a mainstream way as cinema does. Even if the biggest film studios for the most part are just trying to fill their ‘LGBTQ quota’, their desire to seem inclusive pushes the standards of non-heteronormative representation further and further.

Moonlight, dir. Barry Jenkins, 2016.

3. Emotional response

Cinema is a medium with the ability of being both incredibly personal and universal at the same time. It tells stories that can reach people all over the world and strike a chord with them no matter their cultural background and personal experiences. The visual language of film should be comprehensible above all differences we as humans might disagree over in our day to day life. Of course, it would be naïve to expect that for example one’s lack of belief in equality could be changed just like that by watching a motion picture that puts non-heteronormativity on an equal footing with its opposite. But promoting stories that involve positive representation of sexual minorities (amongst others) and normalise it, is invaluable. Cinema can change our outlook on the world and, most importantly, evoke a whole array of emotion within the viewers. After all, that’s the whole foundation of film as an art – provoking an emotional response in viewers. Movies make us empathise with characters we previously maybe wouldn’t have felt sympathy for in real life, they make us reflect, and often, show us that there’s more to the world than our own convictions and prejudices. One of the most important examples of that would be the case of Brokeback Mountain (2005, A. Lee), which introduced mainstream audiences to the idea of queerness existing even out in the remote and rural parts of United Stades, and a love between two cowboys – character usually associated with hegemonic masculinity that stigmatises homosexuality.

4. Societal impact

Throughout history and up till this day, film has been used a tool to influence and affect audiences, also as a part of political propaganda. Since it’s clear movies evoke strong emotional responses and can not only strengthen, but also shape people’s beliefs, it only makes sense they can also be used as a tool for positive change. Film industry’s input into pushing for diversity in the media has a big part in making LGBTQ community a part of the mainstream. Nowadays, we have gay and lesbian protagonists in pictures produced by the biggest film studios in the world, characters who have their own voices and stories to tell, or transgender actors working for Disney. Non-heteronormativity isn’t just reduced to the part of a sidekick ‘best gay friend’ anymore. Exposure to ‘the different’ has a huge impact on society, because, as mentioned before, it makes it real, tangible. To put it bluntly, it’s hard to imagine that in a mainstream consciousness stories touching on male homosexuality could still be reduced to hurtful stereotypes (that for example decades of the romantic comedy genre pushed for), if it’s been exposed to deeply moving and authentic stories like Philadelphia (1993, J. Demme) or Brokeback Mountain (2005, A. Lee). Just like back in the day non-heteronormativity has been presented as something to fear – for example in the film noir genre, nowadays the rising amount of positive and honest depictions of it is doing wonders for the overall societal acceptance and openness to the stories that don’t fall into the ‘straight, white and male’ category.

Brokeback Mountain, dir. Ang Lee, 2005.

5. …And the representation itself

As we already have established, films can have a tangible impact on how we perceive non-heteronormativity as individuals and as society as a whole. They influence our views and emotions, and make issues that we sometimes wouldn’t even have been exposed to in real life become an actual part of our world. The most important bit of it all though, is that filmgoers might have a chance to find themselves represented on the silver screen. In a world that still struggles with understanding what non-heteronormativity actually means and why it’s not something to be frightened of, positive portrayals of e.g. LGBTQ characters can be somewhat trailblazing. Imagine that you’re a teenager coming to terms with your sexual identity, and suddenly you find yourself represented onscreen by a fully fleshed out protagonist whose role in the film doesn’t boil down to mannerisms or other characters making fun of them. If the movie tells you that you’re just like everyone else, isn’t it easier to actually believe in?

Moonlight, dir. Barry Jenkins, 2016.